Who should pay to clean up the oil patch’s Alberta mess?

By Regan Boychuk

The legacy of a century of oil and gas development in Alberta is much more than just riches. There are almost a half-million oil and gas wells, well over 400,000 kilometres of pipelines, and tens of thousands of assorted facilities that played a part in bringing wealth to governments, to Calgary office towers, and to regular Albertans’ pocketbooks.

But Alberta’s conventional oil and gas industry has long been mature and now is well into terminal decline, haunting the province with the spectre of cleaning up a hundred years’ poorly regulated mess.

In fact, the issue of how to reclaim many billions of dollars’ worth of environmental liabilities has grown to such proportions that I believe it is the single biggest issue facing Alberta today and threatening our tomorrow. And it could spill far beyond the province.

Last year, the oilfield service lobby asked for half a billion federal dollars to clean up old wells, but the Trudeau government demurred. Rebranded as a half-billion dollar ‘loan’ this year, the Petroleum Services Association of Canada’s request had the support of the Alberta government, but did not find it’s way into the federal budget.

Instead, the world’s richest and most powerful industry will get $30 million in federal dollars to clean up wells whose owners have gone bankrupt.

How did this problem grow so big and what can be done now, as the conventional oil and gas industry declines, provincial government royalty revenues shrink, and Albertans adjust to a life of austerity?

Northern Badger court case confirmed industry responsibility for clean up

Alberta’s oil and gas industry was dragged into the modern age on June 12, 1991. After three-quarters of a century drilling more than 100,000 wells, the oilpatch was finally going to be held accountable for its environmental liabilities.

Not only were depleted wells going to have to be safely sealed (abandoned, in the industry’s parlance) and the sites properly reclaimed, but most importantly, neither of those responsibilities could any longer be avoided through bankruptcy.

In its decision in the Northern Badger case that day, a panel of Court of Appeal of Alberta judges unanimously ruled that “abandonment of oil and gas wells is part of the general law of Alberta enacted to protect the environment and for the health and safety of all citizens.” The responsibility to properly abandon a well was binding on all who become licensees of oil and gas wells, even in bankruptcy.

Unfortunately, the good effects of the court ruling were short lived.

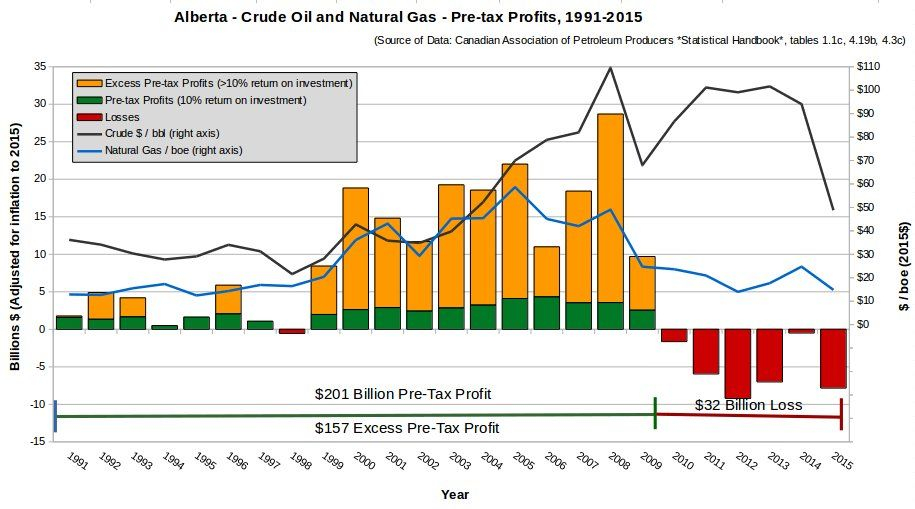

In the 25 years since Northern Badger, Alberta’s conventional oil and gas sector has generated over $169 billion in pre-tax profit for the enjoyment of their executives and investors.

In the same period, regulators allowed the accumulation of many billions of dollars’ worth of unfunded environmental liabilities for cleanup of hundreds of thousands of oil and gas well sites. Estimates of potential cleanup costs reach well into the hundreds of billions of dollars.

Reclaiming an oil or gas well site to near the land’s original capacity involves much more than simply plugging the well. Spills and leaks must be remediated, access roads dug up, and top soil replaced. Risks include contamination of soil and groundwater.

The cost of plugging a well runs into the tens of thousands of dollars, assuming no complications. The cost of remediating a well site, however, can easily run into the hundreds of thousands. When significant leaks or complications are encountered, the cost can reach into the millions for a single well.

Environmental clean up should have priority over all claims in a bankruptcy

The Badger case was the first time Canadian courts considered the intersection of bankruptcy and the environment. Northern Badger Oil & Gas Ltd. had declared bankruptcy and sold all but seven depleted wells to pay off creditors.

The Energy Resources Conservation Board, Alberta’s regulatory authority at the time, ordered the bankruptcy receiver to carry out proper abandonment procedures, safely sealing the seven wells at a cost of more than $200,000.

The court case hinged on whether the Bankruptcy Act requires that the assets in the estate of an insolvent well licensee should be distributed to creditors, leaving the bill for duties of environmental safety – such as safely abandoning and reclaiming depleted wells – up to the taxpayer. The court had to determine whether the bankruptcy receiver had to obey the regulatory order.

In lower court, Justice Jack MacPherson decided environmental cleanup took a back seat to the banks.

“This was incorrect,” the highly regarded legal scholar Dianne Saxe wrote at the time in the Windsor Review of Legal and Social Issues. Saxe, who is currently the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario, explained why it was fortunate the appeals court reversed his ruling:

“The logical conclusion of the Justice’s argument would be that a trustee in bankruptcy could ignore all provincial statutes if they would thereby save money, including dumping hazardous waste in a school yard if that were cheaper than using licensed disposal sites as required by provincial legislation.”

Ruling sent shock waves through oil and gas industry office towers in Calgary

In the appeal court ruling, Alberta Chief Justice Herb Laycraft concluded that a well licensee’s compliance with environmental orders could not be based on whether it might affect distribution of funds to creditors under the Bankruptcy Act.

Those holding well licenses “cannot pick and choose as to whether an operation is profitable or not in deciding whether to carry it out,” the chief justice wrote. “If one of the wells… should blow out of control or catch fire, for example, it would be a remarkable rule of law which would permit him to walk away from the disaster saying simply that remedial action would diminish distribution to secured creditors.”

The Supreme Court of Canada confirmed the ruling by refusing to hear an appeal by industry.

Alberta’s Appeals Court made clear that, in effect, environmental cleanup should enjoy a super-priority over even secured lenders to ensure regulatory obligations were respected in bankruptcy.

Alberta regulators interpreted the ruling to mean they had the power to hold companies jointly and severally liable to clean up their mess. If a company couldn’t cover the expense, regulators could go after its executives. And if those executives couldn’t cover the costs, regulators could go after the company that sold them the wells and their executives.

That threat of accountability sent shockwaves through corporate office towers in Calgary and beyond. By the next summer, the Globe and Mail was warning that “quitting the board could become a growing trend among directors who are becoming increasingly concerned they will be held personally liable for financial commitments their companies are unable to meet.”

Oilpatch executives didn’t have to worry for long though. Regulators relinquished their power to protect Alberta taxpayers and the environment not long after the courts confirmed they had it.

“You can’t just drill wells and walk away from them”

Alberta had a real super-priority for a year and a half, from the Northern Badger decision until December 1992 when the new Progressive Conservative premier Ralph Klein struck a deal with industry to subvert it.

But before it was traded away, the super-priority was having a significant effect on how industry was operating.

By the time 1991’s corporate annual reports were due, the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants was insisting individual companies acknowledge their share of many billions in reclamation costs. “It’s certainly going to hurt,” the regulator’s manager of drilling and production John Nichol said at the time. “But that’s the oil and gas business. You can’t just drill wells and walk away from them.”

“New posses of environmental private investigators are fanning out to catch industrial polluters and make them clean up messes,” the Calgary Herald reported a year after the decision. “Bankers, calling the crackdown self-defense, lead teams of experts such as engineers, soil scientists, water and air quality labs in a dragnet called environmental audits and due diligence. The policing kicks in every time loans are sought for projects or property sales. Loans are refused unless cleanups are done, under stern new standards crafted for the financial community by the Canadian Bankers Association.”

By November, the newly-combined oilpatch lobby – the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers – had released a comprehensive report on how to meet provincial environmental guidelines and clean up polluted land and tear down unused facilities. Organizers expected between 80 and 100 for a seminar explaining their report; more than 320 showed up. Interest was described as phenomenal.

And then, Premier Klein brought it all to an end.

Share This Article:

- Tweet